Cheryl Whitehead

Solo

Mona thought I'd pull my trumpets out

of a burning house and then come back for her.

That was her joke. At Juilliard every time

I turned, some brash young cat came flying in

on fire to show me up, and in his eyes

the tired line, Oh, you're a girl. Go play

the flute, or better, go be a wife. You're cute

enough for that. I sat in practice rooms.

I locked the door. Up and down the scales

I went. The patterns became a part of me

like Mona did when we met. My teacher played

with the New York Philharmonic, and I could see

the doubts he had. He thought, Oh she can play

but she'll never get a big-time job. Not here.

And so I dreamed of Mahler Five and Pictures.

I imagined Bernstein's voice and Mehta's

as I rode the number two downtown to school.

I gigged so much that one night Mona asked,

Should I jot my name in your appointment book?

She sacrificed a lot. I mean it's different

living with a person who stays upstairs

all hours, every single day replaying

the same solo parts until they're carved

into the attic timbers. Mona said

that Shostakovich, Strauss, and Hindemith

would haunt our house long after we were gone.

Last year, Mona got sick. Fatigue. Shortness

of breath. They diagnosed a heart infection.

I brought her home. For seven months she lived

with tanks of oxygen beside her chair.

In our twenty years together, Mona came

to almost every concert here in town.

She'd wave from box seat three before the lights

went down. Her favorite concert was when I played

solo trumpet on the Pines of Rome.

She told me that was the best I ever sounded.

This season is my last with the orchestra.

I'll gig in town with brass quintets and such,

but I can't stand seeing another woman

staring down on stage from Mona's seat.

When I'm practicing, I listen for her steps

and for the teapot yodeling. I hear

her rummaging for cups, her voice echoing

Elaine, come on! I've made our toast and tea.

Leningrad Rehab

—When Shostakovich composed the Fifth, he had begun

the sobering sequence of official castigations

alternating with 'rehabilitations' he was to experience

to the end of his life.

—Richard Freed

"My problem is the symphonies I write,"

admitted a man who wore half-inch-thick glasses.

Around the circle, the gathered patients groaned

until a red-haired guard raised his hand.

The composer rose and crossed the room. He sat

on a stool behind a small upright piano.

"Under normal circumstances," he said,

"you'd hear the strings play slowly, espressivo."

Closing his eyes, he fingered the first few bars.

An older gentleman, who never talked,

hummed the tune off-key.

"And then the harps

enter like someone walking up the stairs."

A blonde glanced at her stitched-together wrists.

"When the solo flute comes in, the harps begin

to play descending octaves."

Leaking through

the room's barred windows, sunshine lit his hands.

He played the Largo movement from his Fifth.

When the older man began to weep, a girl

who'd drowned herself in drink took hold of his arm.

The group's sobs drowned out the man's left hand

stretching the notes of the brooding double basses.

Up the keyboard Shostakovich's fingers

moved as he brought the solo oboe in.

Solemnly, doctors stood in doorways and wept.

Janitors exhaled and leaned against

their mops. Their tears dropped into soapy pails.

"In unison, the harp and celesta play

this solo near the end, and then the strings

play pianissimo and die away."

The chord expired. Doctors wiped their cheeks

with handkerchiefs as the red-faced guards hovered

near Shostakovich. The sun began to set.

Ice crystals spread on panes.

Requiem for a Trumpet

"I guess a fish is playing my trumpet now,"

she tells the cameraman whose eye is fixed

somewhere beyond the girl who could have drowned

but didn't, thanks to God and the weakened roof

she drove an ax blade through with frantic whacks.

"I never thought they'd come, and it was hot.

My daddy got so sick; I thought he'd die,

but then a helicopter picked us up.

I miss my silver trumpet."

The girl looks down.

Joining the buzz of passing fishing boats

and swarming mosquitoes, the camera motor whirs.

"Do you have anything else you want to say

before we pack our stuff?" the director asks.

The cameraman zooms in on the girl's face.

Just out of frame are cars turned upside down,

and next to one small tilted house lie piles

of people's things: a door, a microwave,

a mildewed queen box spring and matching mattress.

"My daddy gave me that horn when I was five.

He said I tried to play it, and then one day

when he was helping me, a note came out.

I won't forget the way my trumpet sounded."

Listening, the cameraman stares through

the long, black tube. The last few feet of film

move through the gate's steel frame and then pop loose.

"Roll's out." He stands, removing the magazine

filled with exposed film. Evening sunlight

flickers off the water's murky surface,

and across the youngster's sunburned face.

"Hey, mister, are we done?" the girl asks.

"Yes. Thanks, dear." The director pats her back.

Just then the girl looks up. She points at something—

a child's shoe floating down the avenue.

Up in the Air

What else have I got to do but read, watch films,

play horn in the living room for movie stars,

or for flocks of ladybugs who've snuck inside

to hear evening concerts of Unaccompanied Suites?

I'm practicing Bach's Prelude from Suite Six.

Up in the Air comes on TV. George Clooney's

playing a jerk who jets around the country,

firing people. I want to loathe this guy,

but I'm too busy plodding through the Bach,

attempting to fake the double stops. God knows

I'm no Yo-Yo Ma, yet I keep trying

to play the transcribed cello music, using

breath as my bow. When more wrong notes than right ones

hang in the air, frustration causes me

to quit. I take a break and watch the film.

On a business trip, George meets a gorgeous redhead.

They talk in a bar and end up sleeping together.

Raising my horn, I urge him: "Be careful, man."

He doesn't heed my warning. Slowly, I

re-play the lilting 12/8 melody.

Halfway through, I lose my concentration.

There's Clooney smiling, knocking at a door.

His lover answers. She's surprised. Behind her,

children dash upstairs, and a man's voice calls,

"Hey, honey, who's at the door?" I stop playing.

My living room goes dark.

An old scene plays, and in this one, I'm the star.

Palm trees stir in the moonlight. Down the street

from where I've parked, a car alarm goes off.

There, in the passenger seat, the woman I love

uses her hands to wipe my tear-streaked face.

"I'm sorry. I didn't mean for this to happen,"

I whimper, wracked with regret because I know

she's married, yet I want her home with me.

I lift my horn to play but I can't think

for all the grief. George sits dejectedly

on the airport train. His cell phone rings. My heart

speeds up. I hope she's calling to apologize.

Instead she asks him, "What were you thinking,

showing up at my door?" This catches me

off guard. I wish I hadn't heard her sexy,

callous voice. But it's too late to strike

her lines from memory or leave in pieces

on the cutting room's cold floor the mess

I made of love.

Now, I don't feel like playing.

I close the book of Unaccompanied Suites

and put my horn away in its black case.

|

|

|

|

| AUTHOR BIO |

| Cheryl Whitehead's poems have appeared in Women's Voices for Change, The Southern Poetry Anthology: Volume VII, The Hopkins Review, Brilliant Corners: A Journal of Jazz & Literature, Measure, Crab Orchard Review, Callaloo, and other journals. She has twice been a finalist for the New Letters Poetry Prize, and the Morton Marr Poetry Prize, and has been awarded grants and scholarships from the Astraea Foundation, the Sewanee Writers' Conference, and the North Carolina Writers' Network.

|

|

| POETRY CONTRIBUTORS |

Catherine Chandler Catherine Chandler

Rebekah Curry Rebekah Curry

Anna M. Evans Anna M. Evans

Nicole Caruso Garcia Nicole Caruso Garcia

Vernita Hall Vernita Hall

Katie Hoerth Katie Hoerth

Michele Leavitt Michele Leavitt

Barbara Loots Barbara Loots

Joan Mazza Joan Mazza

Kathleen McClung Kathleen McClung

Becca Menon Becca Menon

Diane Moomey Diane Moomey

Sally Nacker Sally Nacker

Stella Nickerson Stella Nickerson

Samantha Pious Samantha Pious

Monica Raymond Monica Raymond

Jennifer Reeser Jennifer Reeser

Jane Schulman Jane Schulman

Katherine Barrett Swett Katherine Barrett Swett

Jane Schulman Jane Schulman

Paula Tatarunis Paula Tatarunis

Ann Thompson Ann Thompson

Jo Vance Jo Vance

Lucy Wainger Lucy Wainger

Gail White Gail White

Cheryl Whitehead Cheryl Whitehead

Liza McAlister Williams Liza McAlister Williams

Sherraine Pate Williams Sherraine Pate Williams

Marly Youmans Marly Youmans

|

|

|

|

|

The most recent addition to The Mezzo Cammin Women Poets Timeline is Jane Kenyon by Susan Spear.

Gail White and Nausheen Eusuf are the recipients of the 2017 Mezzo Cammin Scholarships to the Poetry by the Sea conference.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

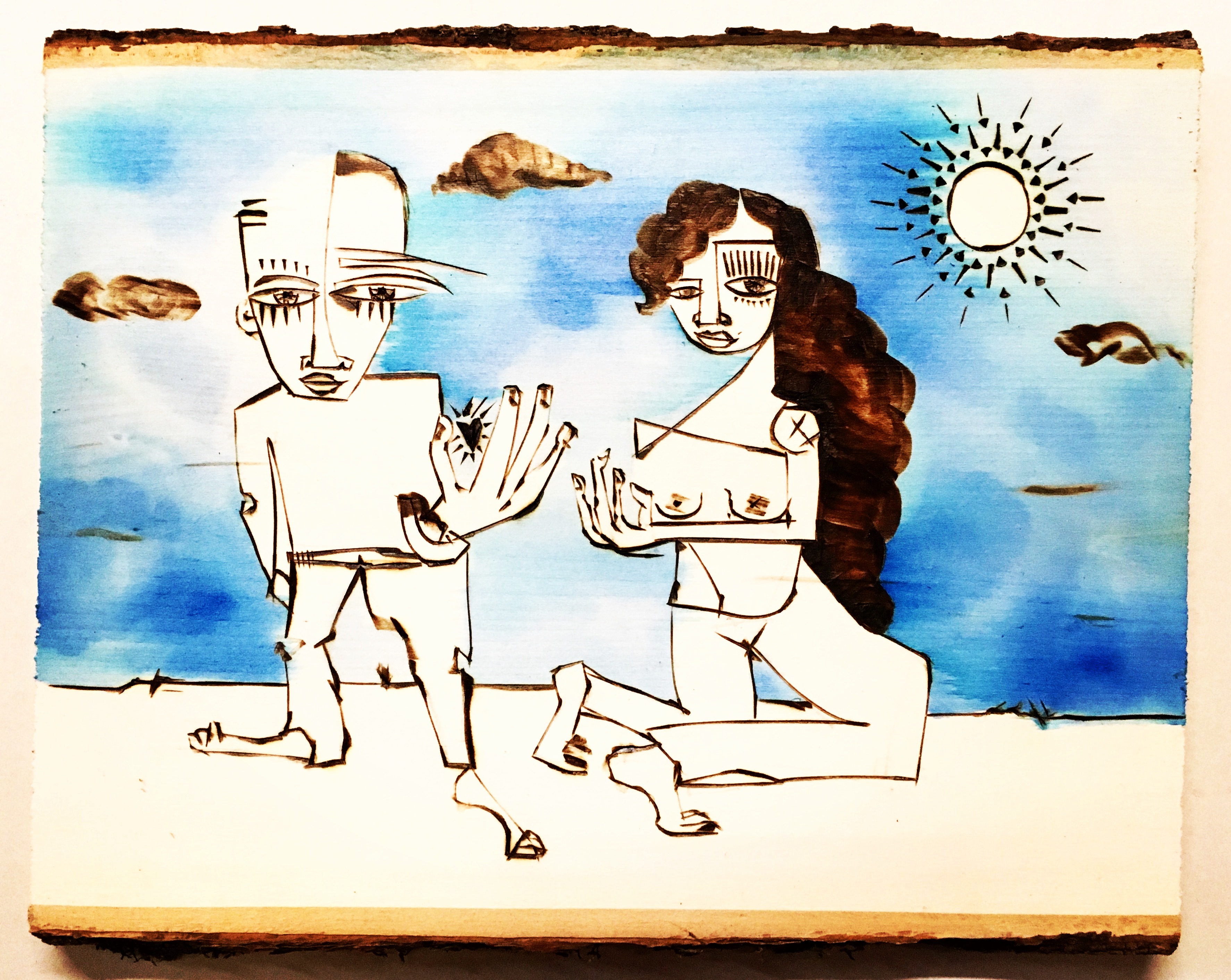

| Alice Mizrachi is a New York based interdisciplinary artist working in the mediums of painting, installation, murals and socially engaged art. Her work explores the interconnectedness of individuals and community through the dual lens of compassion and empathy. Through figurative work that reinforces both personal and community-oriented identity, Alice aims to inspire creative expression and a sense of shared humanity through art.

Alice has worked as an arts educator for nearly twenty years for a variety of organizations including BRIC Arts, The Laundromat Project and The Studio Museum in Harlem. As a pioneer in the field of socially engaged art at the local level, Alice has been recognized and selected to develop arts education curriculum for organizations such as HI-ARTS (Harlem, NY), Dr. Richard La Izquierdo School and Miami Light Project. She has also been a panelist discussing community-engaged art for events at Brown University and The Devos Institute of Arts Management.

As a painter, Alice maintains both a studio practice and an extensive body of work as a muralist. Her work have been featured in exhibitions at the Museum of the City of New York, the National Museum of Women in the Arts, UN Women and the Museum of Contemporary Art in DC. She has been commissioned as a mural artist for projects in Amsterdam, Berlin, Tel Aviv, and across the United States by organizations and museum including: Knox-Albright Museum, Buffalo, NY; Worcester DCU (Worcester, Massachusettes); Wall Therapy (Rochester, NY); La Mama and Fourth Arts Block (NYC); Miami Light Project (Miami, FL); and, Chashama (Harlem, NY), among others.

Alice's mural and installation work has been constructed in galleries and public spaces as part of site-specific arts education and community development projects. Her work often engages local neighborhoods and reflects positive visual responses to social issues. Her process activates a shared space of love, hope, optimism and healing as a means to connect with participants. Frequent topics include identity, unity, migration and the sacred feminine.

Alice and her art have been featured in a variety of publications including the book, 2Create, Outdoor Gallery: New York City, the New York Times, and Huffington Post and The Architectural Digest. She has a BFA from Parsons School of Design and was an instructor at the School of Visual Arts in 2015. Alice was also the co-founder of Younity, an international women's art collective active from 2006-2012. She has received grants from The Puffin Foundation and The Ford Foundation. Her recent projects include a residency in Miami with Fountainhead, a residency with Honeycomb Arts In Buenos Aires and a mural with The Albright Know Museum in Buffalo. Alice currently holds a studio space at The Andrew Freedman Home in the Bronx. Her upcoming projects include a workshop/ panel at Brown University and a book release in Summer 2017.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|