Chelsea Woodard (Featured Poet)

Female Collector

Story hoarder, keeper of notes folded

in Latin class, stubs of dulled drawing pencils,

bits of wool sheared from the neighbor's ewe

(dyed pink or glossy white, like pearls),

drawers full of music boxes, the petty feuds of girls

(detailed in journals: grade 2, grade 9), coins

unearthed from extinction: Swiss francs, lire.

An entire life is possible to fold

away. The adolescent faces of girls

you grew up with: round, blonde-framed, penciled

in a litany of proms and first dates, adorned with pearls

worn by mothers and grandmothers. This older you

savors the dusty film forcing a U-

turn back to that time abroad, Cyrillic alphabets and rubles

pocketed as proof you watched the Neva purl

against its banks, that you never folded

your hand when it came to risk. The future pencils

in a calendar filled with the birthdays of girls

now in their thirties, swaddling baby girls

who stare from photographs, their wide eyes trying to figure you.

So many dried tubes of paint, so many saved pencils—

graphite and charcoal, white. They are precious as coins.

Here is a cigar box of shells; here is a flag folded

by somebody. Three separate sets of heirloom pearls.

The needles your mother used to teach you purl

one—all those uneven stitches a girl

has to learn. Bright colored paper folded

into origami cranes; the names of those you

once loved creased, faded by time, marked

by post stamp, scribbled in archival pencil.

The vision locks on a self-portrait drawn in pencil,

your own eyes bodiless, black-centered pearls

that swim up through the dark like krugerrands

sunk in a shipwreck. This is the record of a girl's

lost treasure, long stowed and loaded onto U-

Hauls, settled in closets, shelved and refolded

every time she's had to fold. Now the rain pounds

luminous pearls on the glass; now another you

smudges the pencil features of the girl.

Portrait of the Collector as a Young Man

I can scarcely manage to scribble a tolerable English letter.

I know that I am not a scholar, but meantime I am aware

that no man living knows better than I do the habits of our birds.

—John James Audubon

When I came to the woods, I knew the ferns

were full of longing. Far from the bells

and white-fenced greens of towns, I have learned

the pardon of mosses, taking up spent shells

that glitter on the shade-dark earth like gold

fillings. Weightless as a carcass

free of flesh, my pack holds

spare instruments: a compass

and charcoal sticks, oil pigments, brushes.

My gun is a light, cold metal rasping

in its leather sleeve. Parting bulrushes

encircling a pond, I gasp

as a bittern lifts, ruffles the surface and squawks

toward the tree line. The bones

of a loon are hollow; no body that walks

can know what it is to skim alone

the tops of hemlocks, to see the sun rise

from a nest of dry branches afloat

in a pine. I wake to the eaglets' cries,

study my sketches, letters I wrote

home to Lucy. What brought me to this place

was not their plumage, alizarin

and umber, nor a man's arrogant race

against where time will drive him—

no. It was the patterns of their flight—

great swooping arcs, marvelous shapes that glide

and shrink to black. The canvas's white

expanse is where their glory hides.

And so I've reimagined all the birds

as silent, stationary things

that cannot render viewers wordless

at the rustle of their wings.

Krugerrands

for B.

Buried just behind the granite post

that marks the outline of my garden, the gold

grows colder. Its presence is my family's lore,

and like most myths, it seems fantastic, old;

some muggy August days it is a sore

that festers in the earth, or else it is a ghost

entombed below my heart—hepatic, dark.

All that the gate of love let in I've tried

to stone out—restoring toppled walls that littered

my pastures with feldspar and quartz—lost

fortunes. Blinded by bullion glitter,

we were naïve to what our secret cost,

and let the myrtle grow. Its rich leaves lied.

I can still see the heaving shovel's mark.

Tower

In the Minchiate tarot deck, this card depicts two

naked figures fleeing from a burning structure.

Running through the granite door,

we never turned to see the great room

burning. Our feet had callouses of char; the air

held the smell of singed hair—

your green eyes lashless, your forearms bare.

But the hillsides were still brimming spring.

Our smoke-clogged bodies bled black riverbeds

of stones, smooth and cool in a bather's fingers.

The fire has left a ring

of ashes on the grass. Lately, I sing

to hear the heaviness of sound

falling, to watch its fullness swell

and drop like rain. Your anger is like rain

that gathers around

the parched flowers, and mine is the ground.

Nostalgia

At seven the sadness was grave, like a dove

in spring half-dark wringing

the light from it. I had known little

of real grief—having been allowed

lazy stretches of aimlessness, love,

a slow buzzing passage of stings

from sharp grasses and bees—the grim rattle

held off by a riot of wildflowers

drowning its song. It began as an art

for remembering: larch needles

and doll clothes, a wing from a moth—a pattern

unbreakable now, held still in the mouths

of propped windows. Curtains part.

In the road, a girl pedals

home, and the low metal creak of the lantern

is blooming I can't get out.

Freeze Line

The angling settlement has been shut up

for months, and all this time we've shuffled

timidly on shifting ice, watching

the sky, the porch thermometer, missing

the dry wood creak of dory oars, the sun.

Anxious for spring, we saw the thawing balsams

as a sign we had come through, wintered this last,

cold-growing sorrow. Today we coast out

to the mouth of the river, past the eagle's nest

and pools broken by deadheads, where the silt sets

rust-like on the banks and the lake rests, washes

over algae-slick rocks. I watch

the wheel rasp under your palms, knowing you watch

for rocks, shallow spots, the darker patches

showing wind—warnings that have been passed

down over a lifetime. Fly rods catch dust

on the camp rafters. Soon, fishermen

will come back to these waters; fathers will show

their sons to tie flies, to cast out toward the drowned

line of trunks, where branches stop, where ice swells the banks

and the cold writes its name on the land.

The Bat

Downstairs, above my writing desk, her body

flitted overhead without my knowing—

something moth-like, a momentary shadow

on the ceiling light, a breath. It took

six passes for her presence to take shape,

for me to look from where I bent to see

the furry underside, her brown wings beating,

silent, in this strange, narrow enclosure,

brushing neither the window nor the wall,

calm almost, as if she trusted something in kind

in here would free her, heard long before I opened

it the sudden door leading her back into the dark.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Jenna Le, Anne-Marie Thompson, and Chelsea Woodard join editor Kim Bridgford at the tenth-anniversary Mezzo Cammin panel at the Poetry by the Sea conference.

Sophia Galifianakis was the recipient of the Mezzo Cammin scholarship.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

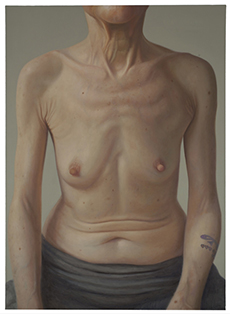

Corpus VI was formed in 2003, when six women figurative painters, who studied together at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, united to curate, exhibit and present our work to the public on our own terms, and launch our artistic careers. The name was chosen because it reflected our shared commitment to figurative representation. Clarity Haynes, Elena Peteva, and Suzanne Schireson were three of the founding members of the group, which organized an inaugural, self-titled show at Philadelphia's Highwire Gallery in the spring of 2005. The exhibition essay was written by Jeffrey Carr, Dean of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. The exhibition was very well-attended and reviewed in several art publications.

The experience of working together to successfully realize this exhibition, as well as the continuous dialogue and exchange of ideas on contemporary figuration, has proven to be greatly valuable to us. Ten years after graduating from PAFA, as our careers have taken us to different locations across the United States, three of the original members, Clarity Haynes, Suzanne Schireson, and Elena Peteva, have come together to reinvent the collective by inviting one artist each to be part of this exhibition that will begin at the New Bedford Art Museum in fall 2015 and travel to other institutions.

Holly Trostle Brigham, Stacy Latt Savage and Laurie Kaplowitz are professional figurative artists, whose strong artistic visions enrich the collective's range and explorations of contemporary representation. We are excited at the prospect of seeing our work all together in new configurations, creating new dialogues. Holly Brigham creates imaginative, narrative watercolors, which tell a feminist story, inserting her artistic persona into art historical narratives and mythologies. Laurie Kaplowitz uses textured paint to create personages that hint at the soul within, alluding to rituals of marking, scarring and adorning the body as an integral part of our human identity and presentation. Stacy Latt Savage combines figurative elements with fabricated structures and shapes to create objects that capture what it looks like to feel human and the complexities of our human condition. Clarity Haynes casts new light on ideas of beauty, femininity and embodiment through her realistic painted portraits of the female torso. Elena Peteva creates allegorical representations of our individual and social states through the human figure and subtle, charged, incomplete signs that invite the viewer's attempt for interpretation. Suzanne Schireson is influenced by her great-grandfather's autobiography as an early plastic surgeon and her paintings examine contradictions surrounding the birth of cosmetic surgery, such as the power to heal and the fostering of insecurity.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|