Holly Painter

Hometown

I talked with a Southerner who was ripping on Detroit.

I stopped him, asked if he wanted to be that guy who

says uncharitable things about other people's hometowns.

He rightly pointed out that I'm from the suburbs, so what

right did I have to be offended, to feel defensive of the

city? I dodged with some rhetoric about how all

of America has a stake in a place that brought us all

wealth and modernity; argued that we can't leave Detroit

behind, can't jettison the arsenal of democracy, the

engine of America, the countless factory workers who

made our cars and our economy. And anyway, what

kind of person spits on a desperate dying town?

I avoided explaining why I once called it my hometown,

why I feel protective of its reputation, why I always

get belligerent with people who casually ask, "What's

the big deal if it collapses? Why bother saving Detroit?"

I avoid answering because I don't really know who's

allowed to claim the city. I left the state, and then the

country a decade ago. Overseas, no one had ever heard of the

little suburb where I grew up. West Bloomfield Township

meant nothing. Michigan drew nods only from those who

followed college football or had to learn the names of all

fifty US states in secondary school. So I said Detroit:

I'm from Detroit. And then everyone knew exactly what

I was talking about. Back home now, I realize I didn't know what

I was talking about. I'm not from Detroit. I never earned the

dubious badge of honor that comes with enduring Detroit's

poverty, its crime, its crumbling neighborhoods and downtown.

I never sat in high school classrooms with sixty students, all

trying to break the cycle of poor families who raise poor kids who

go to poor schools and drop out to raise poor kids who

go to poor schools... That wasn't my reality, wasn't what

my childhood was like. Detroit was the Pistons, and we all

wore our Isaiah Thomas gear on gameday. Or we went to the

Joe to watch the Red Wings win the Stanley Cup for Hockeytown.

Garage bands, punk, fast cars, big stars. That was Detroit.

As a kid, I was proud of "my city." Who was going to explain to me the

subtleties of appropriation or why Detroit wasn't really my hometown?

All I wanted was to be from somewhere. I thought I was from Detroit.

Ruin Porn

I did the ruin porn thing--found the living

room in the elevator shaft of the old Packard Plant

and the graffitied skate park someone built

on one of its upper floors, somewhere in the middle,

far from the smashed out windows and walls

and the sheer drop off of which thrill seekers

roll old cars. And, in 2010, I went to see

Jane Cooper Elementary School. Full of living,

breathing children only three years before, the walls

were, by then, torn down by metal scrappers, and plants

grew inside. Rotting books were piled in the middle

of classrooms and shattered computers littered the building.

When I left the historic 1920's school building,

climbing over an avalanche of files, there was nothing to see

outside. The school had been surrounded by a thriving middle-

class neighborhood once, but by 2010, there wasn't a single living

soul left, just acres and acres of wild brush and desiccated plant-

life where everything had been razed for an office park whose walls

never went up. I never breached Central Station's marble walls,

though I picnicked in front of the old deserted building

many times and even half-seriously planned

to break in some quiet night with friends to see

the arcades and platforms that Amtrak abandoned a life-

time ago, leaving a magnificent Doric edifice in the middle

of Corktown. The train station is the gold standard for the middle-

class kids who come to take Instagram pictures of crumbling walls

and rows of burned down houses on streets where people still live.

When the city condemns but doesn't tear down another historic building,

when DPS announces the latest slate of school closings, they go see.

I did it, too. A "suburban urban destroyer," one Detroiter called me. A transplant

for the afternoon. A local tourist. A rubbernecker who planted

herself there, hoping for a train wreck, hoping to find herself in the middle

of chaos. I didn't take anything. I didn't break anything. I just wanted to see.

I didn't see people, though. I didn't see the No Trespassing signs on the walls.

I wandered for hours through trashed empty buildings

that were beautiful and sad without ever talking to anyone who lived

around there. I planned restorations and salvations, thought I could waltz

in there and meddle and manage and fix it. I destroyed by building

a whole new city in my mind without seeing that it's already alive.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

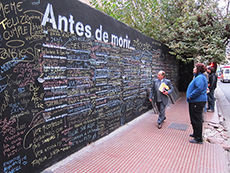

| Candy Chang: Meant as a singular experiment, the Before I Die project gained global attention and thanks to passionate people around the world, over 500 Before I Die walls have been created in over 70 countries, including Kazakhstan, Iraq, Haiti, China, Ukraine, Portugal, Japan, Denmark, Argentina, and South Africa.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|