Crisis Modes: Ancient Egyptian Forms and Modern Women Poets

by Marsha Bryant & Mary Ann Eaverly

t key flashpoints across the twentieth century, Muriel Rukeyser, H.D., and

Ágnes Nemes Nagy invoked ancient Egypt to respond to crises in

different parts of the Western world. Confronting the failed promise of

social systems—including capitalism and communism, each poet adapted

Egyptian sources to craft an ethical stance in the face of catastrophe.

Traditional forms had failed, so these poets sought to re-form modern and

contemporary poetry as they called for social reforms. They surveyed their

dead, looking for signs of new life. Ancient Egyptians' emphasis on the

dead's continuing agency in the Underworld offered a regenerative past in

the face of a troubled present. Moreover, Egyptian literary and artistic

forms provided these poets with different schemas than their more familiar

Greek counterparts. Moving beyond the Classical tradition—and modernist

reinventions of it—Rukeyser, H.D., and Nemes Nagy found new ways of

assembling the long poem and the poem sequence in the twentieth century. In

doing so, these Western writers expanded their creative process by

including Egyptian culture and ethics. This essay draws on our respective

disciplines of modernist studies and Classical archaeology, expanding on

our lecture for the inaugural Poetry by the Sea conference.

The dilemma that the Classical tradition poses for women writers is well

known: a compromised cast of female mythic characters and a canon of mostly

male authors. Consider the Muses, Pandora, Eurydice, Helen. Even the rich

variety of Classical poetic forms (including epic, lyric, and epigram)

links primarily to heroes such as Hercules and Odysseus—and to the warrior

band motifs of the Trojan cycle. Twentieth-century women poets from Amy

Lowell and H.D. to Rita Dove and Carol Ann Duffy have taken on the

Classical tradition by reclaiming powerful goddesses, reinventing heroes,

and giving voice to women characters. A. E. Stallings renews formal

patterns with ironic poetic voices drawn from myth, and Ange Mlinko

migrates iconic mythic patterns beyond a poetics of women's voices. The

poets we examine here show us another way out of the Classical dilemma:

turning elsewhere.

As we shall see, Rukeyser, H.D., and Nemes Nagy venture beyond the focus on

female figures that drives Classical revisionist mythmaking. In fact, all

three turn ultimately to male Egyptian figures (Osiris, Amun, Akhenaten).

Western women poets' interactions with Egyptian myth and culture receive

less attention than their work engaging the Greco-Roman world—even in

feminist literary criticism and media coverage of contemporary women

writers. Although previous commentators have not linked these poets, all

three drew on ancient Egypt to craft creative responses to modern

cataclysm: an American labor disaster, the London Blitz, and the 1956

Hungarian Revolution, respectively. In the face of such catastrophic

events, why did poets as diverse as Rukeyser, H.D., and Nemes turn toward

the ancient cultures of the Nile? Specifically, how did Book of the Dead, "Hymn to the Aten," and pharaonic sculpture shape

each poet's response to contemporary states of emergency? How can their

crisis modes inspire twenty-first century poets?

Rukeyser and H.D.'s poems draw on the Egyptian Book of the Dead as

well as the Osiris myth; H.D.'s and Nemes Nagy's reference sculptures of

the 18th Dynasty pharaoh Akhenaten and his "Hymn to the Aten" to cross gender boundaries. These Egyptian artifacts provide the

poets more maneuverability than extending or revising the Classical

tradition. At the same time, Rukeyser's The Book of the Dead, H.D.'s The Walls Do Not Fall, and Nemes Nagy's Akhenaten sequence extend

women's war writing beyond home fronts and combat zones (Rukeyser

responding to class war). These texts are also among each writer's most

ambitious works. The Book of the Dead and The Walls Do Not Fall were, respectively, Rukeyser's and H.D.'s

first long poems; the Akhenaten poems were Nemes Nagy's longest poetic

sequence.

Rukeyser's Osiris Way

An American poet, Rukeyser came of age as a writer during the

socio-economic crises of the Great Depression, publishing her first volume

in 1935. When she visited the British Museum in 1936, Rukeyser was so

struck by its illustrated copy of Book of the Dead that she later

studied E. A. Wallis Budge's translation at the New York Public library

(Dayton 24, 49). Earlier that year she had studied newspaper accounts of

the Hawk's Nest tragedy, an industrial disaster in West Virginia that

killed at least 764 workers. Union Carbide financed a project channeling

part of the New River under Gauley Mountain to the nearby hydroelectric

power station. Tunneling revealed an unusually large deposit of nearly pure

silica, shifting the project toward a highly profitable mining operation.

The company quickened production without providing workers with protective

masks, causing many of them to contract deadly silicosis from the heavy

dust. Struck by the ethical implications, Rukeyser traveled with a

photographer to Gauley Bridge, West Virginia, where she conducted local

interviews. Drawing from all of her research, the poet overlaid this

contemporary American disaster with the ancient Egyptian text in her long

poem, The Book of the Dead (1938). It consists of 20 poems that

offer a panoramic perspective on the event: situating the event within

American history, the landscape, myth, and testimony from local

residents-including workers. For Rukeyser, the stricken worker's bodies

indicated a national body in need of healing.

Instead of turning to Classical elegy for her source form, Rukeyser chose

the Egyptian funerary text Book of the Dead. Buried with mummies to

help the deceased navigate the Underworld and live on, this polyvocal and

variable text is more accurately called in English Book of Going Forth by Day. It is not a continuous narrative with a

consistent voice, but a collation of hymns, spells, instructions, and (in

some versions) illustrations. Popularly misunderstood to be "the Egyptian

Bible," Book of the Dead is a contingent text with no canonical

order. Rukeyser taps its "internal diversity" to assemble her long poem out

of "different poetic styles, subjects, and documents," adopting what

Catherine Gander calls "a heterogeneous composition method" (191, 197).

Because Rukeyser's source text is modular instead of linear, it opens new

possibilities for modern poetry. In the "Absalom" section, the poet alludes

to the ancient Egyptian text to give voice to one of the dead workers: "I

open out a way, they have covered my sky with crystal. / I come forth by

day, I am born a second time" (667). Many spells in Book of the Dead

offer ritual instruction for "coming forth," "going out," and "opening up";

for example, Spell 9 is "For going out into the day after opening the tomb"

(Book of the Dead, 37). For Rukeyser, this perpetual process of opening out influences her depictions of the workers' death as well

as her poetic form.

News coverage of the Hawk's Nest disaster led to Congressional subcommittee

hearings in 1935 in which workers, doctors, company representatives, social

workers, and others testified. Rukeyser works this heterogeneous material

into her poem, paralleling the Judgment of the Dead in her ancient source.

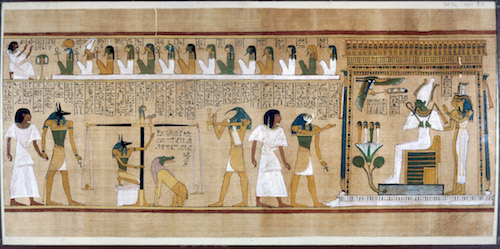

To avoid eternal torment in the Underworld, ancient Egypt's dead had to

account for themselves and weigh their hearts against "the feather of

righteousness" (Book of the Dead 27). We see this process in the Book of the Dead buried with the scribe Hunefer (19th

Dynasty), from the second millennium BCE (Figure 1). Hunefer's heart and

the feather are each placed on the scale of Maat, goddess of order. If

Hunefer's heart weighs less than the feather, he may move on to the

afterlife. If not, he will be eaten by a monstrous deity. In this

illustration, the jackal-headed Anubis (god of embalming and guardian of the dead) presides while the ibis-headed scribe god, Thoth, waits to record the result. As with many copies of Book of the Dead, this one integrates text and image.

Page from the Book of the Dead of Hunefer, from Thebes, Egypt, 19th

Dynasty, circa 1275 BCE.

British Museum, London, Great Britain, Photo Credit:© The Trustees of

the British Museum / Art Resource, NY, Image Reference: ART192986

Rukeyser's poem invokes its ancient predecessor by including an array of

voices, some proving more truthful than others. In "The Doctors" section

she incorporates conflicting medical accounts from the hearings: Dr. L. R.

Harless (employed by the company, and thus untrustworthy), Dr. Leonard

Goldwater (who also interprets x-ray images), and Dr. Emory Hayhurst (who

explains the progression of silicosis). In another section, afflicted

worker Mearl Blankenship testifies in writing that he "wake[s] up choking"

and expects to die (664). For Rukeyser, the truest hearts belong to the

workers, their families, and other affiliates (especially Mrs. Dora Jones

and Philippa Allen). Michael Thurston rightly notes that for the most part,

Rukeyser's "male speakers who wield great institutional power…do not

fare well under her editing hand" (74). Ultimately, Rukeyser calls for an

accounting of capitalism itself as well as the company that exploited these

workers. Just as the trials in Book of the Dead enable passage

through the Egyptian Underworld, the workers' trials will eventually lead

to the passage of safety laws. Through Rukeyser's poem, the dead workers'

labor "can rest and rise forever" in perpetual resurrection-like their

Egyptian predecessors who navigated the Underworld and crossed the

Celestial River (Rukeyser 680).

Unlike its Classical counterpart, the Egyptian Underworld offers a dynamic

afterlife instead of a dismal realm of gray shades. Moreover, it proves

more maneuverable with portals the dead can enter with the right

incantation: the Seven Gates and the 21 "mysterious portals" of the House

of Osiris, god of death and resurrection (Book of the Dead 135-37).

Rukeyser's early reviewer Philip Blair Rice recognized the poem's rendering

of Gauley Tunnel as "the Osiris way," pointing out that "the tunnel is the

underworld, the mountain stream is the life-giving river, the Congressional

inquiry is the judgment in the Hall of Truth" (qtd. in Dayton 122).

Moreover, the name Hawk's Nest likely suggested to Rukeyser the

Egyptian deity Horus (son of Osiris and Isis, goddess of fertility); his

sons assist the soul's journey through the Underworld. Rukeyser's

Underworld imagery appears most fully in the "Power" section, which

descends to a "world of inner shade" before the poem pursues various

openings out in "The Dam" (676). Here West Virginia's New River and

hydroelectric power take on mythic resonance as the celestial river that

the Egyptian dead must cross (the Osiris way, our Milky Way). At the same

time, as Stephanie Hartman contends, "the river emerges as the main figure

for the power of the working class that has been suppressed and usurped"

(220), a rising tide that can ultimately bring forth social change.

In her culminating section ("The Book of the Dead"), a "tall woman" who

carries "the book" appears as "a fertilizing image" (686). While she could

be the Isis figure that Tim Dayton suggests in his analysis (112), we see

her as an embodiment of Rukeyser's Ur-text itself: the Egyptian Book of the Dead transmitting itself to modern readers who are now

"finishing the poem" (686). Rukeyser's text ends by ushering its dead into

the living history of a renewed nation, where they become "seeds of

unending love" (687). Book of the Dead was a "democratic" text in

its availability "to anyone who could copy, or afford to have copied"

excerpts from a source text onto linen or papyrus, as Leonard H. Lesko

points out. Indeed, the name (and sometimes image) of the deceased appeared

in individual versions. Women could also have these books made for them,

and may have even taken part in their composition (195). This degree of

accessibility marks another advantage the ancient text afforded Rukeyser.

The key images, form, myths, and material history of her Egyptian source

helped her confront social crisis and injustice.

H.D.'s World-Father

During the Blitz, American expatriate H.D. wrote the first part of her long

poem that would become Trilogy—The Walls Do Not Fall (1942).

The poet drew on her considerable knowledge of ancient Egypt to reckon with

this immediate crisis; Adalaide Morris points out that H.D. lived "only

blocks from the anti-aircraft batteries in Hyde Park," and thus well in

range of German bombers (123). She read widely in Egyptology, venturing

beyond the standard English-language works by James Henry Breasted and E.

A. W. Budge to explore books on archaeology, divinity, hieroglyphs,

literature, and sculpture. Like Rukeyser, whom she met in 1936, H.D. had

seen Egyptian artifacts in the British Museum. But Egypt was more immediate

for her because she had witnessed the Tutankhamun excavations when she

toured the Valley of the Kings in 1923. H.D.'s itinerary also included

Luxor, Cairo, and Karnak. The latter site proved especially significant to

her poetry because many of its monuments had stood for millennia—a stark

contrast with St. Paul's Cathedral and other London landmarks damaged in

the Blitz. Writing amidst some who found poetry useless in wartime, H.D.

drew inspiration from the sacred status that writing held for the ancient

Egyptians. As Susan Stanford Friedman explains, her "quest for the sacred

is not an escape from war," but a hope "rebirth and regeneration" (136).

Like Rukeyser, H.D. saw an ethical dimension in ancient Egypt that she

found lacking in the modern West.

Instead of turning to Classical epics such as The Iliad and The Aeneid, she grounded her response to the Battle of Britain in

Egyptian culture. H.D. assembles a pan-Mediterranean pantheon inTrilogy, invoking as major goddesses Isis in The Walls Do Not Fall, Aphrodite in Tribute to the Angels,

and Mary/Mary Magdalene in The Flowering of the Rod. Each part

consists of 43 individual lyric poems that interweave Egyptian,

Greco-Roman, and Biblical figures. Although lyric itself was originally a

Greek poetic form, H.D. frames her poem with the Egyptian deities Isis and

Osiris. Isis anchors H.D.'s "original great-mother" trinity; Mary K.

DeShazer argues that she is the "source of divine female wisdom and love"

that wields "a healing power unparalleled in Greek mythology" (H.D. 47;

DeShazer 166). According to Egyptian mythology, Isis gathers the pieces of

her dismembered husband, Osiris, after his brother murders him. She

restores Osiris to life and then procreates with him, producing the god

Horus, divine protector of Egyptian pharaohs. In H.D.'s poem the

Isis-Osiris myth furthers her aims of restoring order to a broken world.

Retrieving "the secret of Isis" allows the poet to reclaim "the one-truth"

that heals division, and perceiving Osiris in the star Sirius allows her to

bridge "resurrection myth / and resurrection reality." Like Rukeyser, H.D.

invokes Osiris to prepare "the patient for the Healer," as she puts it—in

this case, Londoners traumatized by the Blitz (54, 48).

H.D. dedicates The Walls Do Not Fall to her partner (Bryher) and to

a sacred place (Karnak). For the ancient Egyptians, Karnak was principle

worship site for Amun, king of the gods, also known to the Egyptians as the

hidden one. When combined with the sun god Re, Amun was chief deity of the

Egyptian state, and thus the divine supporter of pharaonic rule. Amun

appears several times in The Walls Do Not Fall: anchoring "the

world-father" trinity with Osiris and Ra, and then supplanting Jesus as

"our Christos." In H.D.'s most extensive treatment he appears as the

"Amen-Ra" figure who returns the poet to her spiritual home in Egypt.

Notably, he manifests male and female attributes with "ram's horns" and

womb-like "belly," becoming a divine "father" through whom the poet is

"mothered again" (25, 27, 30-31).

H.D.'s physical rendering of Amen-Ra alludes to the New Kingdom pharaoh

Akhenaten, who would also inspire Nemes Nagy. Akhenaten had returned to the

cultural imagination because archaeologists had discovered colossal statues

of him at Karnak between 1923 and 1925—a major find since his successors

destroyed most of his statuary to protest his radical religious reform.

Akhenaten had replaced Egypt's panoply of deities with the worship of one

god, the sun disc Aten. In parallel fashion, H.D. hails "the new Sun / of

regeneration" to create "new paeans," reanimating what was a traditional

ancient Greek poetic form, (#14, #17). Susan Edmunds points out that the

poem's reference to "the sun-disk" recalls Akhenaten's new solar religion,

while her characterization of Amen-Ra as a "doubly sexed god" alludes to

the pharaoh's sculptural image. (Edmunds 42, 44; H.D. 31). Puzzling

scholars, these statues depicted him with a rounded belly and hips more

typical of women. Physiological and psychological theories emerged to

account for this anomaly, including a 1939 article in International Journal of Psycho-analysis, which H.D. had read. She

was also familiar with Sigmund Freud's discussion of Akhenaten in Moses and Monotheism, published in English that same year. By

superimposing Akhenaten's image over Amen-Ra's, H.D. moves beyond

biological essentialism to reconfigure gender in her epic poem.

In addition to the monumental stability and gender fluidity H.D. found in

pharaonic sculpture, she saw Karnak as a "stone papyrus" that proclaimed

the enduring power of writing (3). Jean-François Champollion, the

first to decipher hieroglyphics, had translated the site's extensively

inscribed walls and columns. Writing in a time of book burning, H.D. found

validation in Karnak's permanent chronicle that the word-in-stone

preserves. In The Walls Do Not Fall, the poet invokes the Egyptian

god Thoth as her major deity of writing; he anchors an artist's trinity

that includes his Classical successors Hermes and Mercury. As the inventor

of hieroglyphics, Thoth was patron god of scribes; he was typically

depicted holding a reed pen and scribal palette (as we see in Figure 1).

H.D. notes that the scribe "takes precedence of the priest" and is

subordinate only to pharaoh. She writes herself into this historically male

role, crossing gender boundaries as she does in refashioning Amen-Ra.

Summoning her fellow poets in Walls, she adorns them in the

trappings of male and female Egyptian deities: the "double-plume" crown of

Amun, the "twin-horns" of Isis (14). Ultimately, H.D. finds the Egyptian

scribe more enabling than the Classical Muse and its gendered division of

male poet, female inspiration.

Nemes Nagy's Stone Pharaoh

For Ágnes Nemes Nagy ancient Egypt also provides a vehicle for coming

to terms with social instability. Written a decade after the bloody 1956

Hungarian revolution, her eight-poem Akhenaten sequence reflects the

upheaval following the Communist clampdown. In addition to this singular

event, the poet also grapples with her country's seemingly never-ending

cycle of social disruption. Bruce Berlind reminds us that Hungarian

national identity has been "continuously threatened with the redefinition

of borders by political upheavals, by changing forms of government, and by

the manipulations of major powers" (Introduction, 4). Akhenaten, an avatar

for social change in his own time, provides a fitting persona for Nemes

Nagy's sequence. The poet draws on his only surviving text, "The Sun Hymn

of Akhenaten" (popularly known as "The Hymn to the Aten"), as well as on

the pharaoh's colossal sculptural image. Like Rukyeser and H.D., Nemes Nagy

had more than a passing knowledge of ancient Egypt, including a "close to

professional's knowledge" of its sculpture (Berlind, "Poetry"). The Museum

of Fine Arts in Budapest, her home city, gave her access to the second

largest collection of Egyptian antiquities in central Europe. Moreover,

Hungary's educational system emphasized Egypt and Asian empires because of

the country's proximity to the East.

Paradoxically, ancient Egypt provides a space for recovering modern events

in a climate of government censorship, which she had experienced

first-hand. An immediate response was impossible because the Communist

government forbade her from writing anything other than children's verses

for 13 years after the revolution (Szirtes, Preface, xii). They also banned

the literary journal that Nemes Nagy co-founded with her husband, and even

imprisoned him. Nemes Nagy begins her Akhenaten poems with an invocation

that reflects this tortured history: "There must be something I could bring

/ to bear on this long suffering" (46). The relationship between the

individual and a totalitarian regime is not alien to Classical mythology.

Antigone, the mythic figure who buries her brother in defiance of the

state, asserts that she obeys older and higher laws than those of earthly

kings. Rather than this well-known story, Nemes Nagy turns to Egypt and

Akhenaten. As John Taylor notes, she addressed Hungarian politics more

explicitly in these poems than in her previous work (789).

"The Sun Hymn of Akhenaten" addresses the solar disc directly in the first

person voice of the pharaoh: "I am your son who serves you, who exalts your

name / Your power, your strength are firm in my heart." He extolls

the Aten as creator and preserver of the world and describes himself and

his wife Nefertiti as the divine receivers and bestowers of the god's

blessings (Lichtheim and Elfert, 96-100). Yet despite his divine status as

pharaoh, Akhenaten was an approachable figure for Nemes Nagy; her

translator George Szirtes points out that she "had developed a kind of

empathetic fascination" with him ("Crystal"). She even made the pharaoh the

persona of her poetic sequence. During Akhenaten's reign depictions of the

royal family depart from conventional rigid stances and strike more

intimate poses, as if we were glimpsing their home life. For example, a

relief from 1345 BCE shows the pharaoh and his wife Nefertiti seated with

their young daughters in one of these seemingly informal moments (Figure

2). Note that Akhenaten (on the left) and Nefertiti both have similar

physiques with rounded bellies and thighs; this gender duality appealed to

Nemes Nagy as is did to H.D. The sun disc suspended above them extends its

blessings to the royal family through rays that end in hands. In "The Night

of Akhenaton,"[1] Nemes Nagy

refers to this specific attribute in her descriptions of light:

"let the sun, / each of whose beams terminates / in one small hand, oh

let it run / its hands across your face."

She humanizes the pharaoh by having him wash his face (47).

The Royal Family (Akhenaten). Egyptian relief. 1345 BCE.

Aegyptisches Museum, Staatliche Museen, Berlin, Germany

Photo Credit:© Vanni Archive/ Art Resource, NY

Image Reference: ART19275

The Akhenaten sequence equates the pharaoh's vision of a new religion with

the poet's yearning for a renewed Hungary. In the first poem ("From the

Notebook of Akhenaton"), the pharaoh's voice fuses with the poet's to speak

of "some deity I could invent to sit aloft omniscient" (46). This

simultaneously describes Akhenaten's elevation of the sun disc as supreme

deity and Nemes Nagy's own desire for stability in her world. "The Night of

Akhenaton" alternates between the bloody 1956 uprising ("and the tanks were

already coming") and an idyllic ancient Egyptian setting. Nemes Nagy, her

husband and several friends narrowly escaped death by leaping barriers and

rolling down a hill when government forces disguised as ambulance

attendants opened fire on a crowd of demonstrators. [2] Although the poem is set

at night, its frequent references to light connect it to the Sun Hymn's

emphasis on the creative and regenerative light of the Aten: "It was bright

/ as summer," she writes" (47). Because of "the pools of light," tanks are

unable to obliterate the bodies of those they try to kill (47). Nemes Nagy

contrasts Egyptian regenerative power not only with military power, but

also with Biblical divinity ("god on the wafer"). Here Akhenaten's

monotheism seems preferable to Judeo-Christian monotheism. The same poem

contrasts the garden of Christ's betrayal (the Judas tree) with "the old

garden, hundreds of thousands in the garden" (the paradise garden of the

Egyptian afterlife). In the penultimate poem, "Above the Object," Nemes

Nagy goes further and finds transcendence and resurrection in the "endless

white" of Egyptian light (52). The sequence ends with "Love," which circles

back to the opening poem's desire for an alternative god and completes the

process of spiritual rebirth: "Now I've invented a new deity."

Significantly, this poem closely parallels the ending of "The Sun Hymn of

Akhenaten" by referring to "lovely Nefertiti," Akhenaten's wife (52). The

Egyptian past offered Nemes Nagy a monotheism that is free of what she

perceived as the failures of modern religion and its secular replacement,

Communist dogma. Thus the Akhenaten sequence becomes her personal "hymn to

the sun" as the poet re-interprets this ancient religious text.

Because the Hungarian language does not mark gender, as Szirtes notes

(Preface xii), the sequence's "I" is not grammatically identified as male

or female, allowing Nemes Nagy to collapse herself with Akhenaton. The

pharaoh provided the poet with a multi-faceted persona capable of

responding to the modern crisis of the Hungarian Revolution: a

gender-bending voice that was social and personal at once. As Nemes Nagy

stated in a 1980 interview, "I felt that the Akhenaton character was

capable of carrying the polysemic indefinable problem of the 20 th century individual" (qtd. in Lehóczky, 166, note 108, p.

166). At the same time, the surviving sculptures depicting this pharaoh are

fixed and permanent, unlike the statue of Stalin that was toppled and

broken during the revolution. Nemes Nagy seeks a similar permanence in her

poems: "In carving myself a god, I kept in mind / to choose the hardest

stone that I could find" (49). Through this ambitious sequence composed in

form, she crafted her vision of a reformed and renewed world.

Rukeyser, H.D., and Nemes Nagy saw Egypt as a foundation for modern ethics

in the face of an increasingly unstable century. And so their poems return

to the "dawn of conscience" [3] they recognized in

ancient Egypt's moral vision. All found endurance in their Egyptian source

material: a healing power in Egyptian myths, an aesthetic inspiration in

Egyptian literature and art. Book of the Dead is not a book of

deeds, so it does not constrain the poets with narratives of heroes and

heroics. Moreover, H.D. and Nemes Nagy found an additional touchstone in

Egyptian art's flexible portrayal of gender during Akhenaten's reign.

Because his portraits are not conventionally masculine, they do not

constrain these poets with one-dimensional gender roles. Yet ultimately,

each poet moves beyond gender in her envisioning of social reform and

renewal. Indeed, the Akhenaten figure opens up new possibilities for

ekphrasis as well as revisionist mythmaking. By venturing beyond the

well-trodden path of the Classical world, all three poets found crisis

modes of expression that helped them make sense of contemporary social

turmoil. (As H.D.'s pan-Mediterranean work shows, these ancient traditions

need not be mutually exclusive.) Rukeyser, H.D., and Nemes Nagy turned to

Egyptian culture because of its differences from the Classical tradition.

Contemporary poets can turn to them for new ways of imagining and making.

WORKS CITED

We would like to thank Edit Nagy, Lecturer in European Studies at the

University of Florida, for translating and discussing Hungarian material on

Ágnes Nemes Nagy.

The Ancient Egyptian Book of the Dead

. Trans. Raymond O. Faulkner. Ed. Carol Andrews. Austin: U of Texas P (in

cooperation with British Museum Publications), 1990.

Berlind, Bruce. Introduction. Selected Poems, by Agnes Nemes Nagy.

Iowa Translations Series, ed. Paul Engle and Hualing Nieh Engle. Iowa City:

University of Iowa International Writing Program, 1980.

---. "Poetry and Politics: The Example of Ágnes Nemes Nagy."The American Poetry Review, (Jan.-Feb. 1993): 5+. Literature Resource Center. Web. 15 Jan. 2013.

Breasted, James Henry. The Dawn of Conscience. New York: Charles

Scribner's Sons, 1934.

Bryant and Eaverly, "Egypto-Modernism: "Egypto-Modernism: James Henry

Breasted, H.D., and the New Past." Modernism/modernity 14.3 (Sept.

2007): 435-53.

Dayton, Tim. Muriel Rukeyser's The Book of the Dead. Columbia: U. of

Missouri P, 2003.

DeShazer, Mary K. "'A Primary Intensity Between Women': H.D. and the Female

Muse." In H.D., Woman and Poet. Ed. Michael King. Orono, ME: National

Poetry Foundation, 1986. 157-71.

Edmunds, Susan.

Out of Line: History, Psychoanalysis, and Montage in H.D.'s Long Poems.

Stanford: Stanford UP, 1994.

Friedman, Susan Stanford. "Teaching Trilogy: H.D.'s War and Peace." In Approaches to Teaching H.D.'s Poetry and Prose, ed. Annette Debo and

Lara Vetter. New York: MLA, 2011. 135-141.

Gander, Catherine. Muriel Rukeyser and Documentary: The Poetics of Connection.

Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2013.

Hartman, Stephanie. "All Systems Go: Muriel Rukeyser's 'The Book of the

Dead.'"

"How Shall We Tell Each Other of the Poet?": The Life and Writing of

Muriel Rukeyser

. Ed. Anne F. Herzog and Janet E. Kaufman. New York: Palgrave, 2001.

209-223.

H.D., Trilogy. Introd. and Reader's Notes by Aliki Barnstone. New

York: New Directions, 1998.

Lehóczky, Ágnes.

Poetry, the Geometry of the Living Substance; Four Essays on Ágnes

Nemes Nagy

, with a Preface by George Szirtes. Newcastle Upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars

Publishing, 2011.

Lesko, Leonard H. "Book of Going Forth By Day." In The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, ed. D. B. Redford. Oxford:

Oxford UP, 2001. 193-95.

Lichtheim, Miriam, and Hans-W. Elfert, Ancient Egyptian Literature, vol. II: The New Kingdom, 1976.

Berkeley: University of California Press: 2006. 96-100.

Morris, Adalaide. "Signaling: Feminism, Politics, and Mysticism in H.D.'s

War Trilogy." Sagetrieb 9.3 (1990): 121-33.

Nagy, Ágnes Nemes. The Night of Akhenaton: Selected Poems.

Trans. George Szirtes. Highgreen (U.K.): Bloodaxe Books, 2004.

Rukeyser, Muriel. The Book of the Dead. Anthology of Modern American

Poetry, ed. Cary Nelson. New York: Oxford, 2000. 656-87.

Szirtes, George. "The Crystal Maze," The Guardian May 14, 2004. Web.

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2004/may/15/featuresreviews.guardianreview36

---. Preface to

Poetry, the Geometry of the Living Substance; Four Essays on Ágnes

Nemes Nagy

, by Lehóczky, Ágnes. Newcastle Upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars

Publishing, 2011.

Taylor, John, " Poetry Today," Antioch Review 63.4. (Autumn 2005):

788-792.

Thurston, Michael. "Documentary Modernism as Popular Front Poetics: Muriel

Rukeyser's 'Book of the Dead.'" Modern Language Quarterly 60.1

(March 1999): 59-83.

[1]

Szirtes's translation uses the alternate spelling Akhenaton.

[2]

Lehóczky refers to this biographical incident in her book

(167, note 124).

[3]

The

Dawn of Conscience

is Breasted's history of moral thought that he grounded in ancient

Egypt. H.D. and Rukeyser knew the book, which the American

Egyptologist published in response to the emerging crisis of WWII

in Europe. For more about Breasted's influence on H.D., see our

essay "Egypto-modernism: James Henry Breasted, H.D., and the New

Past," Modernism/modernity 14.3 (September 2007): 435-53.

|